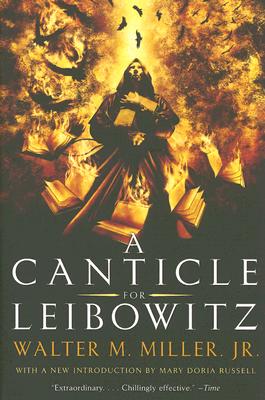

While I mostly write about new (or at least new-ish) books here, my to-read pile has a backlog occupying several years and a multitude of bookshelves and boxes before we even get to the actual stacks of books forming a retaining wall next to my bed. It’s a haphazard collection, assembled piecemeal and somewhat at random. Rather like the library in A Canticle for Leibowitz.

If you’re into classic science fiction, you’ve probably heard of this one even if you haven’t read it. It’s one of those titles that turns up on lists, has yet to go out of print, and while some of it reads pretty dated now (even allowing for a nuclear apocalypse in the interim, it’s hard to read communication technologies that were cutting edge in the 1950s as futuristic, and the only woman in the book with a name is dead), it’s pretty easy to see why it’s on such lists, and why people continue to read it. The back matter on the mass-market paperback copy I picked up years ago is evocative:

In a hellish, barren desert, a humble monk unearths a fragile link to 20th-century civilization. A handwritten document from the Blessed Saint Leibowitz that read: pound pastrami, can kraut, six bagels—bring home for Emma

Canticle was published in 1959 and bespeaks an awareness of atomic annihilation that was still present, albeit less immediate, when I was growing up in the 1980s. Thus the survival of something as pedestrian and random as a shopping list (though, as emerges during the story, the survival of this particular shopping list is less random than that back cover text might imply) perfectly sets up the story of struggling to preserve fragmentary knowledge against not only the vicissitudes of time, but against deliberate attempts to obliterate it. What is preserved might be so removed from its original context as to make no sense; or, it might tantalizingly hint at that context which has been lost. Both occur in A Canticle for Leibowitz, a fix-up that links together three distinct stories separated by time, but all centered on a Catholic monastery located in the American Southwest following a nuclear apocalypse.

Climate change has pretty much replaced nuclear war as the thing that will destroy humanity in SF or disaster fiction, but for decades a mushroom cloud was how the world would end—definitely with a bang rather than a whimper—and day after-type stories were pretty common. What’s rather remarkable about Leibowitz is its setting—though given that one of the functions of monastic communities in the past had been the preservation of knowledge, it’s a logical one—and hints of the supernatural in the ancient figure who turns up from time to time, seemingly looking for the Second Coming. This setting and this character tie together narratives spaced centuries apart, yet in each one history has a way of repeating, or at least of rhyming with what came before. This is a pretty major theme of the book overall, and it’s one of the ways the monastery continues to justify its existence and resistance to outside interference: its goal is to salvage and preserve, even knowledge that its community believes should not be used and which their predecessors were killed for having and trying to save.

That question—whether there exists knowledge so dangerous that it ought to be destroyed—is never really resolved, and in a way that’s the point of the book. It’s an argument against the notion that human history is a story of progress: that today is better than yesterday, and yesterday was better than last year, and last year was better than a century ago. The prospect of nuclear annihilation was a hell of an argument against this idea all by itself, but in Canticle this is just the mechanism for a wider-ranging observation: that much of human history is striving to keep from falling over our own feet. This manifests in a few different ways beyond the frequent existential threats to the monastery, its principles, and its ways of life: by the end of Canticle, the shadow of a mushroom cloud once again appears on the horizon, even as humanity prepares to step off planet.

While much of the novel has the feel of a western, with attendant scenes of violence and threatened violence—quite aside from the looming shadow of nuclear annihilation—a lot of what’s important in Canticle happens in conversations. Here, the tensions of the novel play out in verbal sparring, often satirical in tone: between prelates and politicians, between the recurring figure of the ancient pilgrim and the brothers of the monastery, between the preservationists of the abbey and the scientists who want to sift through that preserved knowledge as they attempt to rebuild civilization. That rebuilding, as the end of the novel shows, is a mixed blessing, but Miller is careful not to blame civilization itself. As Douglas Adams wrote, people are a problem.

Despite significant elements of the book being very much of their time, it’s easy to see why Canticle has endured as a classic. The questions that it asks are never really settled; that’s the point. And if the informational storage technologies it depicts seem somewhat antiquated, plenty of librarians and archivists will tell you that in a lot of ways, physical media are easier to preserve, and to access later, than digital ones. In that sense, A Canticle for Leibowitz remains timeless.